Wednesday, Nov. 13, 2019

There was no one like him. He had stories. He was born in 1916 on the south side and could tell me first hand, about the Stockyards.

His father worked there. And he told me about his father, who died a year and a month before I was born. Grandpa Mike (Mikhail – he was from Russia) was, among other things, a cooper. I thought of him as I used tools I inherited – passed down to my dad from him. A cooper is a barrel maker – that’s one of the things he did at the Stockyards. Ages later, I sharpened up his two-handed draw knife and fit in a piece of flooring, perfectly. He had a real monkey wrench, too. And a gun he’d always shoot straight into the air on New Year’s Eve, Dad told me.

I still have the last letter he wrote to my dad in Jan. 1950 – right before he died.

Grandpa owned a grocery store/butcher shop around Roosevelt and Damen, from the 20s to the 40s. When Dad was a little kid, Grandpa would fire up the Chandler, and he’d accompany him to South Water Market, where they would pick up fresh meat and groceries for the store. The business and Grandpa’s investments are what saved the family from the worst of the Depression. In the late 40s, he and Grandma left for sunny Phoenix, where my uncle and his bride lived. He died there at 67.

The memories lived on in my dad, and he passed them on to me. Dad grew up in the Al Capone era, where he was sent off with a bucket to a back door establishment and would return with the bucket filled with beer. The Cubs were good then, and were often in the World Series. Dad was at Wrigley, age 16, selling ‘unofficial’ score cards, when Babe Ruth called his famous homer. Dad didn’t see it – he told me he was avoiding Andy Frain, who eventually caught up with him and his friends and not-so-gently, kicked them out of the park.

Dad and his buddies, particularly Willy Patete – a short, blond- haired Italian whose mom would serve up gigantic bowls of pasta – would hop on the back of fruit trucks and steal watermelons for a forbidden treat in the summer.

He was in a club. They met in one of the kid’s basements. These days, the members might be called gang bangers. I don’t know that they did anything really bad, outside of what you’d see in the Dead End Kids or Bowery Boys films, but the hierarchy of the local clubs graduated into the 42 Gang, which was Triple AAA for Al Capone’s big league.

Did you know Al Capone dearly wanted to buy the Cubs? He wanted Babe Ruth to manage.

Dad joined the Navy when the War came. He wanted to be a Marine, but was just past the age limit. He went to Hawaii, Okinawa, fought in the Battle of Leyte Gulf. He told me the stories. I remember him and my uncles exchanging war trials and tribs, over and over at family gatherings.

Now Dad’s ship – the USS Preserver (before it was scrapped, it’s last mission was salvaging the remains of the space shuttle, Challenger) – was in fact, hit by a torpedo while it was in dock. Harrowing. Afer Dad passed, I found a journal I hadn’t seen, documenting his experience. ‘War is hell,’ he would tell me, over and over.

The little book justified that. I never learned how right he was. In college, I fought for peace (high lotto number – I’d signed up for the Naval Reserves, but optioned out before I committed), a.k.a. avoiding VietNam.

But Dad, grim reality aside, tended to trump up his experiences to look even larger than life than he already was, in his little boy’s eyes.

I was about five – we had just moved into the new house – which stayed in the family 48 years. One Sunday, I climbed onto the couch to be with my hero, who was relaxing in his shorts and dago-t. Mom wasn’t far away, washing dishes in the kitchen.

“Daddy, what are those marks?” I inquired, as a younster would, pointing at three scars on Dad’s leg.

“That’s where Daddy got shot up in the war,” he explained, about to fade into War reverie.

“No he didn’t!” I heard my mom’s voice. “Don’t believe him – he’s full of baloney.” She came in, drying a dish. “Those were boils he had on his leg. He didn’t get shot up in the war.”

Dad smiled.

When he retired, we used to shoot pool at a local tavern on Thursday nights and have a few beers. That’s where we really bonded.

I’m glad I ran the video camera one night at the kitchen table, while dad just talked. Mom was gone already, and his last stories flowed freely.

He taught me how to play ping pong. He took me to Maxwell Street near Hull House, where street vendors sold everything they could get their hands on, and famous blues musicians picked and wailed in every doorstep. He loved the Three Stooges and went downtown to see them play music and work out their act before they started to make films. He was a boxer and fought Golden Gloves as a teen. He taught me how to ride a bike and play baseball. He had a way of throwing and catching that hailed back to when he was a kid in the 20s and 30s, and, btw – that was when his dad took him to Maxwell Street. He made sure I towed the line – the best, and hardest thing of all. His sense of humor was great, and he passed that on to me, too.

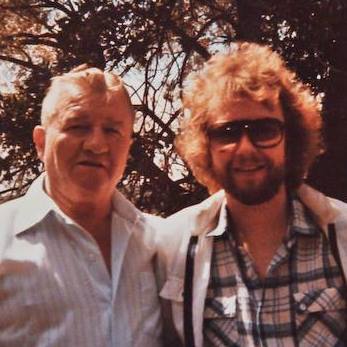

And he gave me (or tried to), the best of that Greatest Generation – his wisdom. See you later, Dad. Sigh, not too long, either.

Beautiful, Randy, and so moving and telling and what a legacy you are moving forward with. Wow! Thanks for sharing this, Sir!